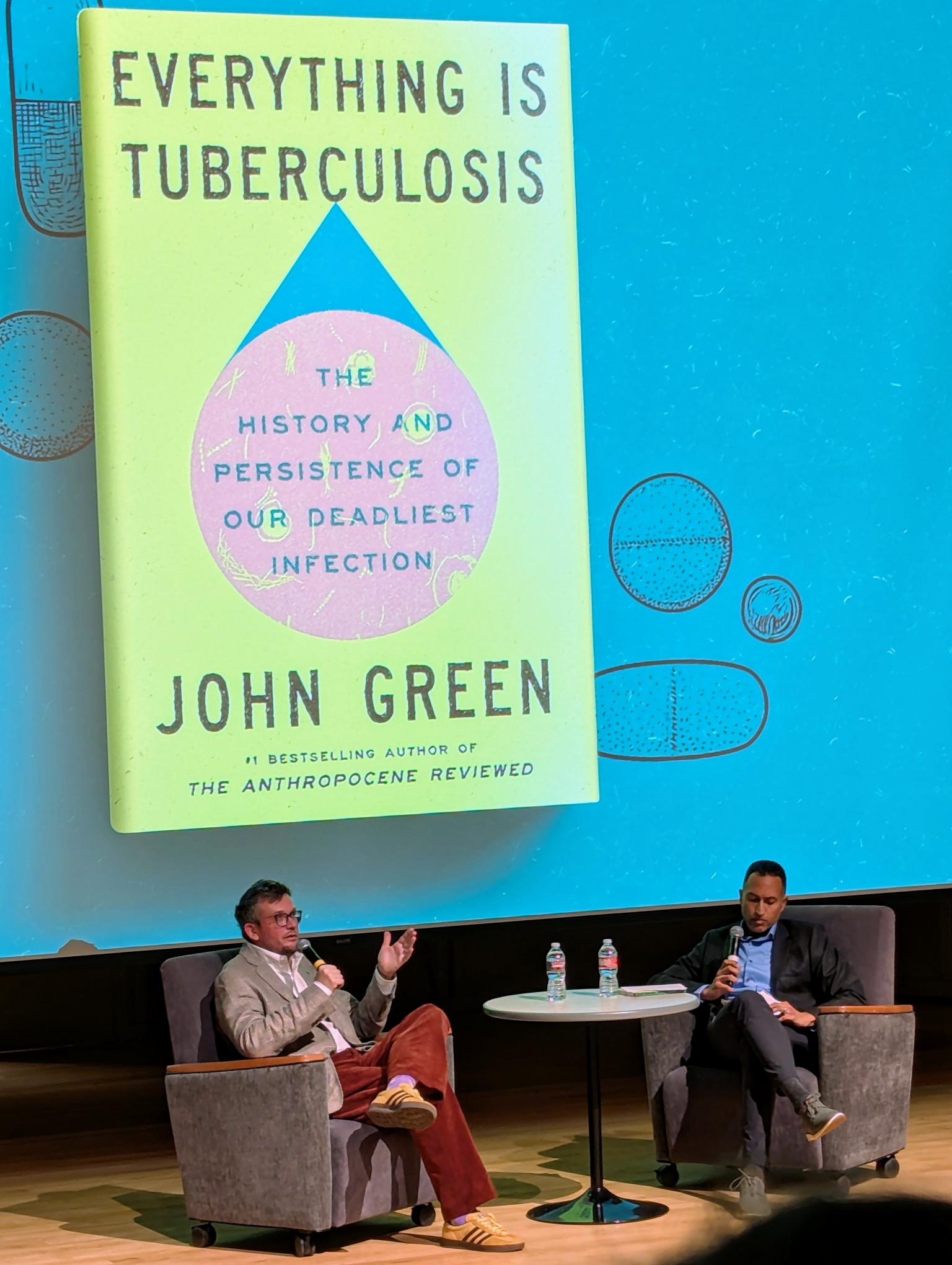

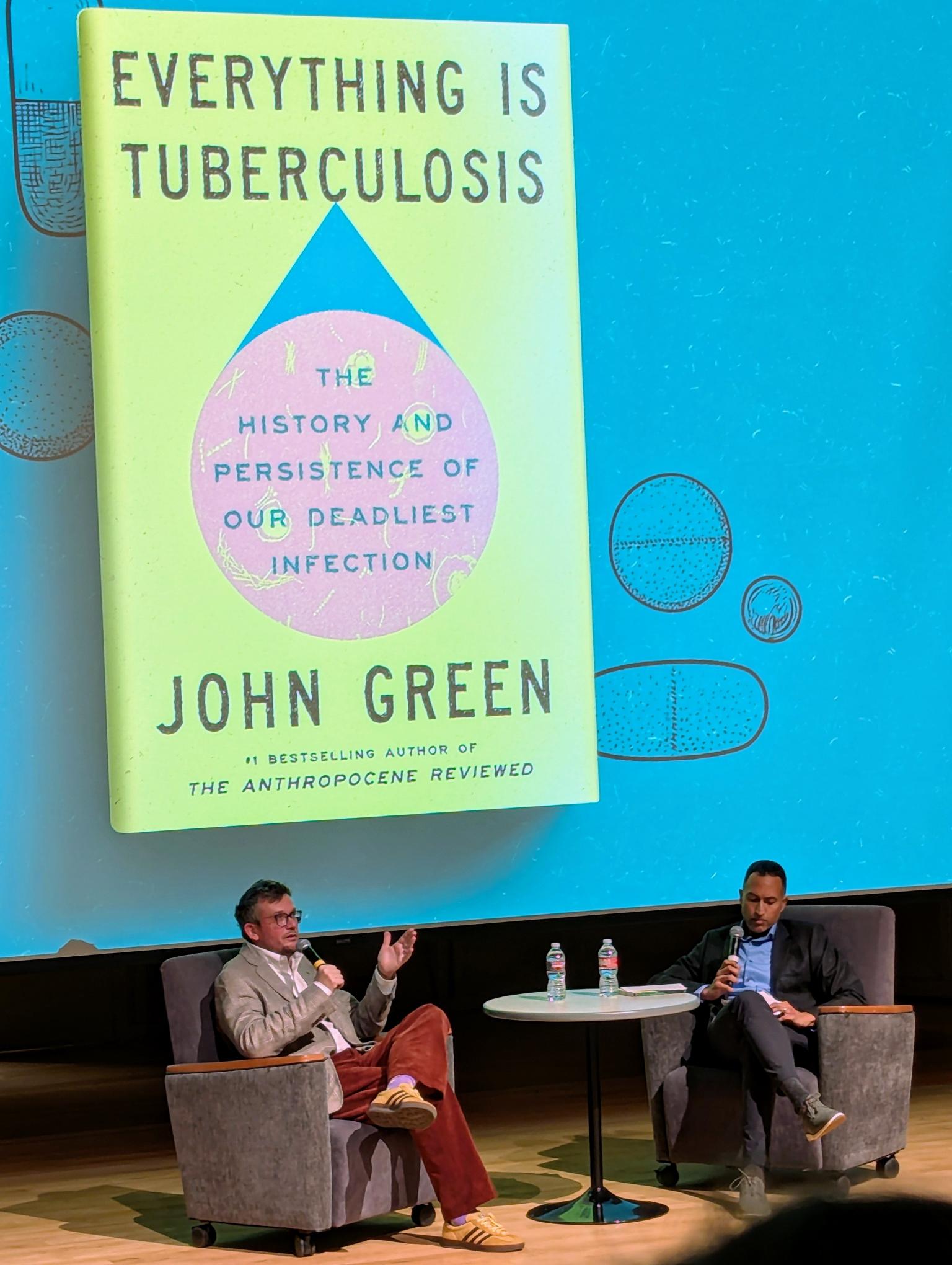

John Green’s ‘Everything Is Tuberculosis’ is reflective and earnest

This article originally appeared in the New York Times.

Tuberculosis kills more people — over a million a year worldwide — than any other infectious disease.

It would kill millions more annually were it not for a fragile system devoted to finding and treating the disease in developing countries. That system, long propped up with the help of funding from the United States, has been jolted by the Trump administration’s recent moves to slash foreign aid. Already, hundreds of thousands of people with tuberculosis worldwide can’t get tests and treatments. The U.S. Agency for International Development, which President Trump has been dismantling, projected worrisome consequences: a 30 percent increase in tuberculosis cases globally, and an influx of patients with drug-resistant cases arriving in the United States.

All of this makes John Green’s new book, “Everything Is Tuberculosis,” incredibly timely. It is, at its core, a plea to readers to care about a disease that doesn’t directly affect them.

Green is best known for young adult novels like “The Fault in Our Stars,” a best-selling tear-jerker about two teenage cancer patients. “Everything Is Tuberculosis” is his second nonfiction book. He’s also a video blogger and, with his brother Hank Green, has built a large and devoted following of altruistic fans who call themselves “Nerdfighters.”

Green seems to have this audience in mind with his expansive, easy-to-read “Everything Is Tuberculosis.” Earnest and empathetic, he tells the disease’s story in a way that can feel at times like his series of educational YouTube videos.

In Green’s telling, he has become obsessed with tuberculosis, seeing it as a window into “the folly and brilliance and cruelty and compassion of humans.” His book’s title is a nod to that. “My wife, Sarah, often jokes that in my mind everything is about tuberculosis, and tuberculosis is about everything,” he writes.

Green first got interested in the disease in 2019, a few years after he became involved in advocacy for other global health causes, when he toured a hospital in Sierra Leone. There, he met Henry Reider — a vibrant, creative 17-year-old who was emaciated by tuberculosis that had grown resistant to standard treatment. The two struck up a long-distance friendship when Green returned home to Indianapolis.

Reider’s story is the heart of Green’s book, an encapsulation of why tuberculosis remains intractable in many poorer countries. After war in Sierra Leone impoverished Reider’s family, he was malnourished as a child, making him more susceptible to the disease. Reider started standard treatment that should have cured him, but his father, distrustful of the health care system, took Reider off the regimen midway through. Later a cocktail of highly toxic drugs failed him, while bedaquiline, a safer, expensive medication that might have worked, wasn’t available.

Green also traces the history of the disease, which is caused by bacteria, usually attacks the lungs and for centuries indiscriminately killed both the rich and the poor. He chronicles the medical advances, most notably the arrival of effective anti-tuberculosis drugs in the 1950s, that have tamed the disease in wealthy countries. (Each year, the United States counts fewer than 10,000 cases, nearly all of which are cured.) The problem, Green writes, is that “the cure is where the disease is not, and the disease is where the cure is not.”

Green makes a thoughtful, considered case for funding tuberculosis programs in poorer countries, weighing practical arguments that might appeal to a skeptic of foreign aid: Such support pays for itself many times over, by preventing expensive infections and improving productivity. It could also safeguard the United States, by preventing the emergence of a resistant superbug that could reignite tuberculosis in wealthy countries. For his part, Green prefers not to think in these terms, focusing instead on what he sees as a moral obligation to care about other people whose lives have just as much value as our own.

In some of the book’s most compelling sections, Green tells the stories of activists like Shreya Tripathi, a teenage tuberculosis patient in India who waged a legal battle against her government to access bedaquiline, which had been restricted because of concerns about overuse and resistance. Another chapter documents an ambitious effort beginning in the 1990s by Partners in Health, a global health nonprofit for which Green is a trustee, to prove that drug-resistant tuberculosis could be cured in poorer countries with the right resources.

At times, Green can be frustratingly vague in assigning blame for the persistence of tuberculosis. The drugmaker Johnson & Johnson, which manufactures bedaquiline, makes a brief cameo when Green accuses it of price gouging and patent gaming (accusations the company has denied). But more often, Green points the finger at abstract forces like “social determinants of health” or “markets” or “our economic systems” or “choices humans made together to deny treatment to people in poor countries.” I was left wanting more about what choices were being made and who was making them.

I was also left wondering how the trajectory of tuberculosis compares with those of other infectious diseases. What’s unique to tuberculosis that makes it so intractable? What was different about other diseases that have been fully or nearly eradicated? Green is so focused on tuberculosis that he devotes little space to these questions.

Tuberculosis is not an easy subject to take on, and Green does an admirable job introducing readers to a disease they would otherwise be unlikely to learn about. His book reads as especially prescient amid the Trump administration’s disruption of health programs around the globe. In a video earlier this month posted on TikTok and Instagram, where he has millions of followers, Green said he wished “the U.S. government could make my new book a little less relevant.”

Add short, eye-catching callout text here.